Sargassum fertilizer transfers heavy metals to vegetables

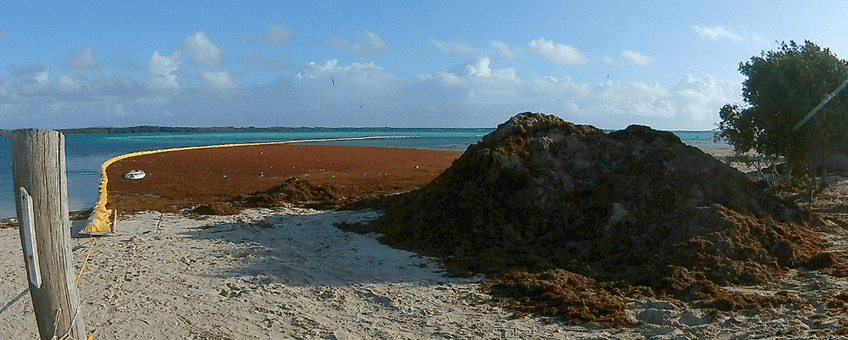

Dutch Caribbean Nature Alliance (DCNA), STINAPA Bonaire, World Wide Fund for Nature – Netherlands Sargassum is a floating brown seaweed that plays several important ecological roles. Although sargassum occurs naturally, due to shifting ocean currents and increased pollution, the Atlantic is experiencing episodic sargassum blooms. Since 2011, the Caribbean has experienced several significant sargassum events, leading to a number of social, environmental and economic issues, particularly in the hospitality and fisheries sectors. Sargassum influxes also threaten the already fragile coral reefs, mangroves and seagrass beds.

Sargassum is a floating brown seaweed that plays several important ecological roles. Although sargassum occurs naturally, due to shifting ocean currents and increased pollution, the Atlantic is experiencing episodic sargassum blooms. Since 2011, the Caribbean has experienced several significant sargassum events, leading to a number of social, environmental and economic issues, particularly in the hospitality and fisheries sectors. Sargassum influxes also threaten the already fragile coral reefs, mangroves and seagrass beds.

The study

To better understand the impact of disposed sargassum, a joint project between WWF-Mexico and STINAPA Bonaire explored whether sargassum-enriched fertilizer promoted faster seed development and if any heavy metals were detectable in the vegetables after harvest. Two planter boxes were used, one filled with 50/50 dried sargassum and potting soil and one with only potting soil.

The results

In general, there appeared to be no significant physical differences (shape or quantity of vegetable production) between plants grown with or without the presence of sargassum. However, samples analyzed at the Radboud University found that arsenic levels were higher in vegetables grown in soil with sargassum. More specifically, bok choy had 37 times, zucchini 21 times, spinach 4 times and sargassum soil 13,5 times more arsenic than their counterparts grown in plain potting soil. Cadmium levels were also higher in plants grown in sargassum-enriched soil, with chemical analysis showing bok choy having 2,5 times, zucchini 3 times, spinach 1,3 times and sargassum soil 2,7 times the amount of cadmium of samples without sargassum enrichment.

In general, there appeared to be no significant physical differences (shape or quantity of vegetable production) between plants grown with or without the presence of sargassum. However, samples analyzed at the Radboud University found that arsenic levels were higher in vegetables grown in soil with sargassum. More specifically, bok choy had 37 times, zucchini 21 times, spinach 4 times and sargassum soil 13,5 times more arsenic than their counterparts grown in plain potting soil. Cadmium levels were also higher in plants grown in sargassum-enriched soil, with chemical analysis showing bok choy having 2,5 times, zucchini 3 times, spinach 1,3 times and sargassum soil 2,7 times the amount of cadmium of samples without sargassum enrichment.

Furthermore, a Wageningen University and Research report titled “Opportunities for valorization of pelagic Sargassum in the Dutch Caribbean”, analyzed sargassum from the same source and found it to have high levels of heavy metals. The full report (pdf; 3,1 MB) is available from the Wageningen University and Research website.

Implications

The health implications of these findings are still unclear. Arsenic can take several forms, both organic and inorganic, where organic levels can be much higher before negative impacts are observed in people. It should be noted that the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has not yet set official thresholds for arsenic. In fact, the EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM) published data in 2010 which stated that there are no ‘safe’ levels of arsenic. Long-term ingestion of inorganic arsenic has been connected to skin lesions, cancer, developmental toxicity, neurotoxicity, cardiovascular disease, abnormal glucose metabolism and diabetes. More research is needed to understand impacts of these higher levels of heavy metals and the long-term effects when ingested.

As influxes of sargassum are becoming increasingly common, countries and individuals will search for innovative ways to use and dispose of this nuisance. Already, some reports have highlighted its use as a building material, animal fodder or fertilizer for home gardens. Until the health implications are more widely understood, it would be wise to limit sargassum use to non-consumable options. This leaves the door open for sargassum to be used as building material (dried and pressed into bricks), biofuel or perhaps fertilizer for decorative plants or construction materials, such as bamboo.

This project was funded by WWF-Netherlands and received support from Radboud University.

Text and photos: Jessica Johnson and Sabine Engel for STINAPA