Protecting fish proves to be key in slowing down invasive seagrass

Dutch Caribbean Nature Alliance (DCNA), Florida International University, University of Amsterdam, Wageningen University Invasive species can pose a direct threat to native species through competition and hybridization. Species that evolved to reproduce and spread rapidly generally have a greater chance at survival, and when introduced to a new environment, can outcompete slower growing native species. This is certainly the case for Halophila stipulacea, a seagrass native to the Red Sea, Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean, which has been rapidly gaining habitat within the Caribbean since its first reported sighting in 2002. This species is quickly outpacing native turtle grass (Thalassia testudinum) and manatee grass (Syringodium filiforme), both of which provide critical habitat, coastal protection and foraging grounds.

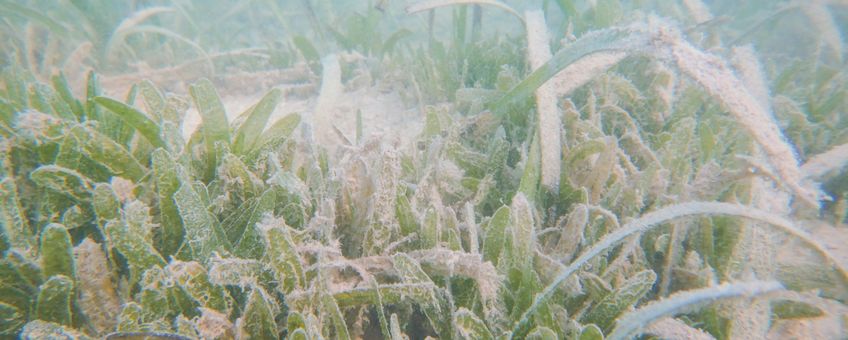

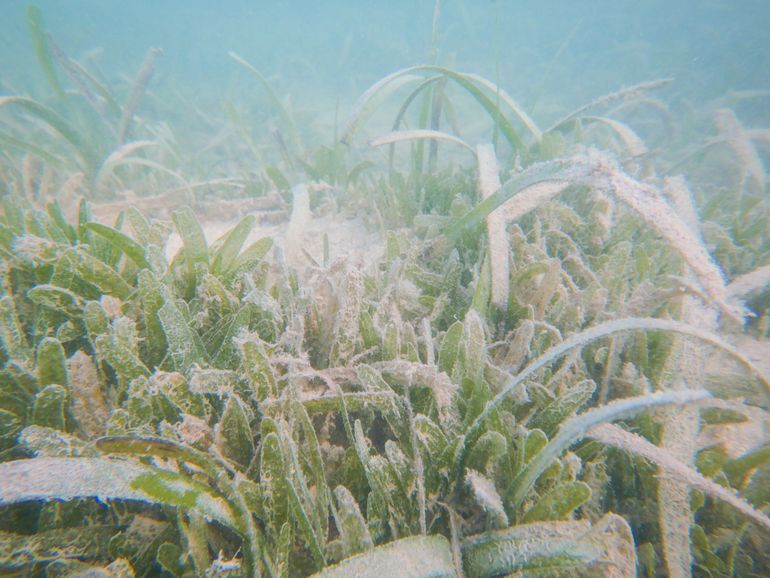

Invasive species can pose a direct threat to native species through competition and hybridization. Species that evolved to reproduce and spread rapidly generally have a greater chance at survival, and when introduced to a new environment, can outcompete slower growing native species. This is certainly the case for Halophila stipulacea, a seagrass native to the Red Sea, Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean, which has been rapidly gaining habitat within the Caribbean since its first reported sighting in 2002. This species is quickly outpacing native turtle grass (Thalassia testudinum) and manatee grass (Syringodium filiforme), both of which provide critical habitat, coastal protection and foraging grounds.

The study

A new study by Wageningen University and Research, the University of Amsterdam and Florida International University worked to improve overall understanding of the controlling factors in the spread of invasive seagrasses. Researchers investigated the influences of local nutrient enrichment (nitrogen and phosphorus) as well as the impact of large herbivorous fish on the growth and expansion rates of Halophila stipulacea. The study took place between 2018 and 2019 within two seagrass meadows: Lac Bay on Bonaire and Barcadera on Aruba.

The results

Nutrients were added to selected seagrass plots at both sides by using slow-release fertilizer. Interestingly, only on Bonaire did these excess nutrients actually result in a reduction of H. stipulacea’s expansion into the turtle grass meadows, while native seagrass was unaffected. The cause is believed to be that on Bonaire, herbivore fish abundance is seven times greater and diversity is 4.5 times higher than on Aruba. Excess nutrients likely enticed more fish to graze, thereby limiting the spread of the invasive seagrass. Native seagrass is more adapted to high grazing pressures. During this study grazing pressure increased after nutrient enrichment, but only the invasive species showed lower expansion rates. In fact, the exclusion of large herbivorous fish (like parrotfish) doubled the invasive expansion rates within sandy patches on Bonaire, further strengthening this theory.

Top-down approach

This study highlights the importance of holistic approaches to ecosystem management. Healthy and diverse fish communities can provide top-down control to invasive species expansion. Increasing grazing pressures can help reduce the competitive advantage of fast-growing species, slowing down invasion of non-native species. The key to seagrass restoration and conservation could lie in protecting the biodiversity of these fragile areas.

To learn more, please find the full report on the Dutch Caribbean Biodiversity Database.

Text: Dutch Caribbean Nature Alliance

Photos: Fee Smulders