Volunteer GIS mapping, ancestral knowledge and a bird atlas: useful insights about citizen science in conservation

World Wide Fund for Nature – NetherlandsTo learn more about this interesting subject from experts and to kick-start four new citizen science projects in Indonesia, Bolivia and Zambia, WWF NL and IUCN NL organised a citizen science workshop in July 2019. We are keen to share some interesting findings with you!

Citizen participation and contribution

As the name suggests, the degree of citizen participation is very important in citizen science. Rosy Mondardini of the Citizen Science Center Zurich marks three levels of involvement in gathering, analysing and using data: people who contribute, collaborate or co-create. This involvement ranges from simply collecting data to participating in all aspects of the research process.

Next, she distinguishes three degrees of contribution. First, she describes volunteer computing, which means that people donate their spare computing resources (such as processing power or internet connection) to a research project. Second, there is volunteer thinking: participants contribute with their brain power, adding skills that are too difficult for computers, such as recognising objects in pictures. The platforms Zooniverse and SciSarter offer many of these people-powered research projects to join. Finally, the provision or collection of data by participants is called volunteer sensing. For instance, photos shared or actively gathered by people to use as data source is a form of volunteer sensing. iNaturalist is a great example of a biodiversity observations database, built by citizen scientists.

Ten principles of citizen science

Margaret Gold from the European Citizen Science Association offers us Ten Principles of Citizen Science. These principles underlie good practice and can support in assessing new and existing initiatives, aiming to foster excellence in all aspects. For instance, one of the principles is that both the professional scientists and the citizen scientists benefit from taking part. Another one is that citizen scientists should receive feedback from the project to increase their involvement. You can read all principles here.

Ethical and legal issues

Anna Jobin from the Health Ethics and Policy Lab explained that the right to science is included in the Declaration of Human Rights (1948). Participatory research principles were developed around 1995, but many questions are still unanswered, such as whose knowledge counts. Studies showed that challenges for researchers and citizens are different: researchers emphasize transparency, while trust and respect are the most important aspects for community members.

Three interesting case studies

To demonstrate the theory in practice, some very inspiring people took the stage during the citizen science workshop and presented their projects. A brief selection:

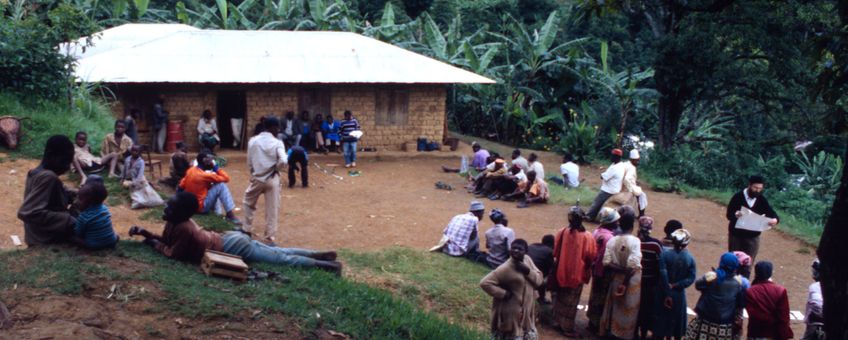

1. Volunteer GIS mapping

Fredy Mbianda from the Center for environment & development in Cameroon explained about the inclusion of local communities in GIS mapping and data collection. He stressed the importance of supporting local communities to give them a voice and to be able to defend their rights. “Please include us, people without a voice, we depend on our land.” Communities can collect data, such as deforestation numbers, straight from the ground with the tool Timby. This helps them to immediately defend their rights.

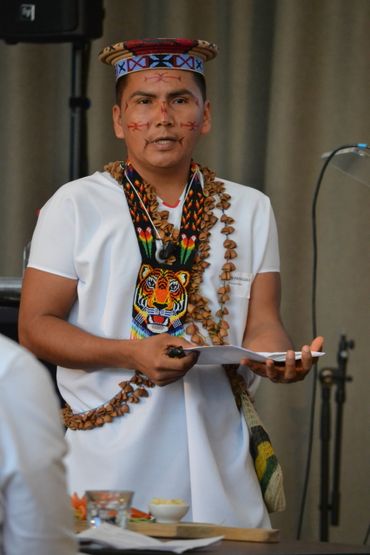

2. Ancestral knowledge

3. How a bird atlas engages people

How do you connect young people with nature? Samuel Ivande from the University of Jos in Nigeria gave a wonderful example: citizen scientists were used to create the Nigerian Bird Atlas. The aim is to map all the country’s bird species, based on valued input from citizen scientists: volunteers who are keen to go birding and submit their observations. These activities generated a lot of energy and more and more people became excited to join the project. Next to the advantage of the conservation of bird species, the project delivered many other positive developments within the community and on the environment. Samuel: “Now we have been able to speak with a collective voice.” As a valuable take-away, he stressed the importance of identifying and organising existing communities instead of creating new ones. The key point should not be to get the data, but to connect people with nature.

More to explore

These were just a few take-aways from inspiring speakers. We did not even mention the project of Alejandro Guardin from IIED about people keeping food diaries, where participants did not just provide data but learned to interpret and understand their own diet. Or the website of Climate Crowd, a crowdsourcing initiative to gather data on how climate change is impacting people and nature. Curious to learn more? Please check out the workshop report.

Best advice?

To wrap up this animated workshop, participants were asked to give their opinion: what would be your best advice to truly engage the community you work with? There were many, but there was one everyone agreed on: listen to the perspective of the people and involve them, from the very beginning!

WWF NL and IUCN NL are working together on the design and implementation of citizen science projects, in a strategic partnership with the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Text: World Wide Fund for Nature

Pictures: WWF NL; Marieke van der Velden