Nature reports

Page 1 of 36 - 354 Results

Every summer there they are again, blue-green algae. Why are they a problem, are they getting worse with climate change and what can we do about them? These are questions that over the past few years the Netherlands Institute of..

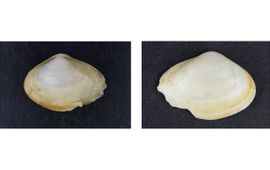

The Asian clam has found its way to the Dutch Wadden Sea. This is shown by field researchers from the Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ). On other locations, the Asian clam has shown to be potentially highly invasive in..

Dunes are considered to be essential for coastal protection. In countries like the Netherlands, where one third of the country is below sea-level, it is crucial to understand how they grow. Sand will play a role, of course, but..

The Netherlands is a delta, a country that exists by the grace of water. Yet only in 1957 a professional ecological research institute for fresh water was established: the Hydrobiological Institute, a precursor of NIOO-KNAW. In..

With a recent publication in the journal Scientific Data, NIOZ researchers have made the data from the SIBES research programme from 2008 to 2021 available to the community. In SIBES, all tidal flats in the Dutch Wadden Sea are..

The Dutch contributing partners of the international MiningImpact3 consortium have been awarded 1.4 million euros. The money will be used to study the long-term ecological impacts of deep-sea mining, as well as the legal and..

The image of the classic nature volunteer – an older man with binoculars and a passion for nature conservation – no longer seems to hold true. A recent study by Wageningen University & Research shows that Dutch people engage with..

Plants in the shade utilize more light for photosynthesis than previously thought. A team of researchers from Utrecht University and Wageningen University & Research (WUR) describe how, in the scientific journal Plant Cell &..

As human populations grow and climate change alters habitats, conflicts with Eurasian brown bears are on the rise. Wageningen University & Research has developed the Human-Bear Conflict Radar, an online tool that uses modelling..

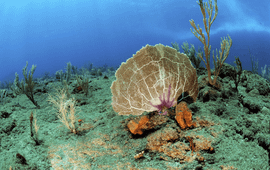

A recent study explored the spread of a disease affecting sea fans in the Dutch Caribbean. Known as multifocal purple spots syndrome (MFPS), this disease is caused by parasitic copepods and has significant impact on the health of..