Slithering settlers: the story of Aruba’s Boa situation

Dutch Caribbean Nature Alliance (DCNA) The boa constrictor is a non-venomous snake species that is native to South America and the Caribbean islands of Trinidad, Tobago and Isla Margarita. Due to their popularity as exotic pets, these snakes have been introduced to other parts of the world, including Aruba. The first boa constrictor was found on Aruba in 1999, and despite efforts to curb their expansion, an island wide population was established by 2005. Between 1999 and 2016, over 4,520 boas were captured and removed from the island. However, even with these measures, the local boa population has continued to thrive. The snakes can reach lengths over 4 meters (14 feet) long and can weigh up to 27 kilograms (60lbs). Although their coloration can vary, they are typically brown, gray and cream patterned, helping them camouflaging within tree canopies. Boas rarely interact with humans but have been known to strike when they are threatened. Although not deadly, their bite can be very painful.

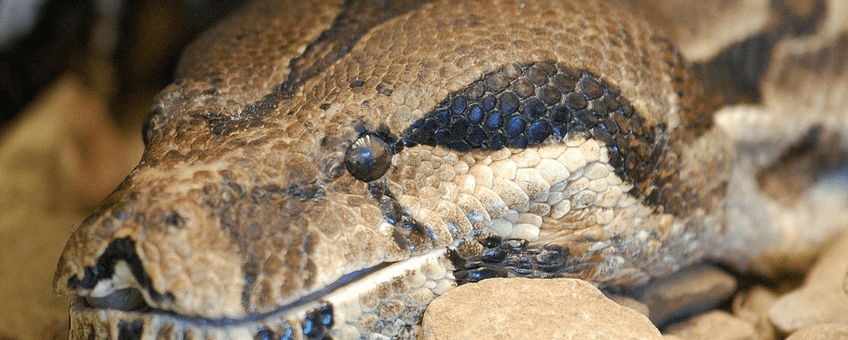

The boa constrictor is a non-venomous snake species that is native to South America and the Caribbean islands of Trinidad, Tobago and Isla Margarita. Due to their popularity as exotic pets, these snakes have been introduced to other parts of the world, including Aruba. The first boa constrictor was found on Aruba in 1999, and despite efforts to curb their expansion, an island wide population was established by 2005. Between 1999 and 2016, over 4,520 boas were captured and removed from the island. However, even with these measures, the local boa population has continued to thrive. The snakes can reach lengths over 4 meters (14 feet) long and can weigh up to 27 kilograms (60lbs). Although their coloration can vary, they are typically brown, gray and cream patterned, helping them camouflaging within tree canopies. Boas rarely interact with humans but have been known to strike when they are threatened. Although not deadly, their bite can be very painful.

Generalist Diet

Boa constrictors are apex predators, meaning they are at the top of the food chain in their ecosystems. In their native habitats, they play an important role in regulating populations of rodents and other small mammals. However, as an invasive species, their generalist diet means they could be a potential concern for a wide variety of native populations. A 2021 study investigated the stomach contents of over 500 captured boas from Aruba. Here, researchers identified over 400 different types of prey, with a nearly even split between mammals, lizards and birds. In fact, with the exception of the seven different bat species known to inhabit Aruba, almost every other type of vertebrate was observed within the stomach contents evaluated.

Boa constrictors are apex predators, meaning they are at the top of the food chain in their ecosystems. In their native habitats, they play an important role in regulating populations of rodents and other small mammals. However, as an invasive species, their generalist diet means they could be a potential concern for a wide variety of native populations. A 2021 study investigated the stomach contents of over 500 captured boas from Aruba. Here, researchers identified over 400 different types of prey, with a nearly even split between mammals, lizards and birds. In fact, with the exception of the seven different bat species known to inhabit Aruba, almost every other type of vertebrate was observed within the stomach contents evaluated.

Rapid reproduction

Boas are of significant concern because they mature quickly (within three years), have a long lifespan (40 years) and produce large litters of offspring (50+) every two years. Left unchecked, this species is able to rapidly reproduce and outcompete native species. Of particular concern is the impact of these snakes on declining native bird populations including the burrowing owl (Athene cunicularia), Aruban parakeet (Eupsittula pertinax), and crested bobwhite (Colinus cristatus). In fact, one boa dissected had four burrowing owls in its stomach. When you consider the native population is estimated at around 200 pairs, this is very significant.

Island wide Impact

Aruba has already tried a wide variety of control strategies. Organized bounty programs were found to be ineffective, as boas can be very difficult to track for inexperienced hunters. There was also a pilot effort to lure snakes into traps using living birds and chicken broth. However, there was limited success given the boa’s preference for ambush predatory behavior. Other methods which have worked in other places, as the temporary release of mongoose or the intentional introduction of a targeted disease, have been dismissed as ecologically irresponsible.

Aruba has already tried a wide variety of control strategies. Organized bounty programs were found to be ineffective, as boas can be very difficult to track for inexperienced hunters. There was also a pilot effort to lure snakes into traps using living birds and chicken broth. However, there was limited success given the boa’s preference for ambush predatory behavior. Other methods which have worked in other places, as the temporary release of mongoose or the intentional introduction of a targeted disease, have been dismissed as ecologically irresponsible.

Overall, the impact of boa constrictors on the island of Aruba has been significant, highlighting the potential consequences of introducing non-native species to new environments. While these snakes may seem harmless in their natural habitats, their introduction to new ecosystems can have far-reaching and unintended consequences. This is especially true for small islands already facing unsustainable threats from rapid urban development and climate change.

DCNA

The Dutch Caribbean Nature Alliance (DCNA) supports science communication and outreach in the Dutch Caribbean region by making nature related scientific information more widely available through amongst others the Dutch Caribbean Biodiversity Database, DCNA’s news platform BioNews and through the press. This article is part of a series of articles on ‘Invasive Alien Species in the Dutch Caribbean”. This article contains the results from several scientific studies but the studies themselves are not DCNA studies. No rights can be derived from the content. DCNA is not liable for the content and the in(direct) impacts resulting from publishing this article.

Text: DCNA

Photo's: Vandy Louw; Diego Marquez; Diego Marquez; Suzanne Hendrik