Bonaire 2050, a nature inclusive vision put into numbers

Dutch Caribbean Nature Alliance (DCNA), Wageningen University & ResearchBonaire, one of the Dutch Caribbean islands, is facing major challenges including managing (mass) tourism and population growth, preventing high erosion rates caused by the constant grazing of free-roaming cattle, recharging fresh water into the soil, increasing the use of renewable energy, adapting to sea level rise and extreme weather events, halting biodiversity loss, and bending the unilateral dependency on tourism. In thirty years, Bonaire will inevitably look different. Current trends will only increase these challenges. What alternative could relieve the challenges and offer a better future for people and nature?

Crossroads

Two outlooks have been developed through a participatory process with key actors from various sectors. The outlooks are a result of a series of design sessions, interviews and workshops with local experts, decision makers and researchers, underpinned by scientific data and field observations. For one of the outlooks, current trends have been extrapolated into the future until 2050. For the other outlook, a vision for Bonaire in 2050 is portrayed, in which nature is interwoven into all sectors. This includes integrating nature inclusive measures, such as rooftop water harvesting, reforestation and greening gardens using indigenous species and growing local food. The researchers calculated how these measures would bend the curves of the projected current trends.

Two outlooks have been developed through a participatory process with key actors from various sectors. The outlooks are a result of a series of design sessions, interviews and workshops with local experts, decision makers and researchers, underpinned by scientific data and field observations. For one of the outlooks, current trends have been extrapolated into the future until 2050. For the other outlook, a vision for Bonaire in 2050 is portrayed, in which nature is interwoven into all sectors. This includes integrating nature inclusive measures, such as rooftop water harvesting, reforestation and greening gardens using indigenous species and growing local food. The researchers calculated how these measures would bend the curves of the projected current trends.

'These outlooks form a basis for dialogue, to stimulate positive change on Bonaire'

Current trends extrapolated

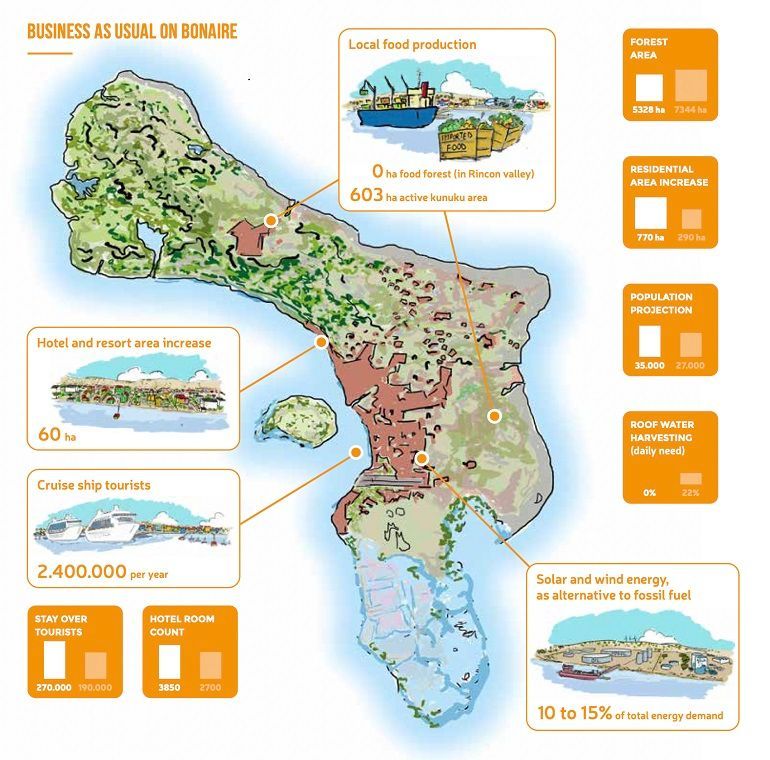

If the current trends continue, by 2050, the population on the island is double that of today. The numbers of cruise ship tourists have increased almost fivefold, and the built-up areas are expanded to accommodate for this. The energy demand has tripled, and the water demand has nearly doubled. Meanwhile access to freshwater is increasingly difficult and costly with the drier climate.

The free-roaming grazers continue to remove vegetation, which further dries-out the landscape. The ongoing expansion of the town makes it increasingly susceptible to flooding and land wash-off. The land becomes less and less fit for growing food and the dependency on off-island imports continues. This dependency makes the island susceptible to fluctuations in world trade and market prices. The shorelines are being built up further, forming a continuous wall of constructions, which in turn threatens the touristic appeal of the island.

The alternative

In a future in which island policies and cultural change stimulate a beneficial partnership for people and nature, the population on the island has stabilized. Urban expansion is restricted to current designated development contours. The number of cruise ship stop-overs has reduced, and the numbers of flight passengers and the population have levelled off, halting urban expansion. There is a clear shift to high-end (eco)tourism with family inns, boutique hotels and country retreats. Most energy is produced by wind-turbines. Households and business buildings are equipped to collect rainwater and solar energy from their rooftops. All energy collected is used over the urban electricity grid, and rural areas store energy on site with batteries. This strengthens the island’s energy self-sufficiency and reduces dependence on fuel imports. Water collected from rooftops and into cisterns is used for watering gardens. It therefore reduces the energy needed to desalinize for production of freshwater. Ponds are also incorporated into the public areas.

All these water capturing measures reduce freshwater and land wash-off, protecting the coral reefs from smothering and excessive nutrient enrichment. Natural watercourses are free from man-made obstructions and the zones around them are revegetated to decrease erosion and increase water absorption into the soil. Construction of new buildings make optimal use of prevailing wind direction, window blinds and shading by vegetation to create a comfortable indoor climate and limit the need for air-conditioning. For new construction projects, the natural vegetation is kept mostly intact; no full clearances take place before construction works begin. On kunukus, shade trees are planted as fence posts, so that grazers are contained rather than allowed to roam freely. Vegetable and fruit tree production has become more common with local entrepreneurs. Fresh local produce is sold to local restaurants, hotels and supermarkets. Vegetable waste is used as fodder for goats that are kept for meat in fenced ranches. In the valley of Rincon, a food forest is developed, which attracts eco-tourism and local activities. Communities and schools also grow food together in local gardens, stimulating the interest in own food production and farming.

'Imagination is critical to sustainable and just futures for life'

These outlooks represent a range of options of the direction the future might take and what can be done to steer one way or the other. They are the basis to engage people in exploring possible futures and their consequences for society. This takes off blindfolds to avoid moving unconsciously into future situations that would be harmful and undesirable. Putting numbers to the outlooks helps people envision a desirable future and how to reach it. These outlooks have been presented to Bonaire’s Island Council on November 15th 2022 and to the general public during the Nos Zjilea cultural event of November 26, 2022, where the work has been endorsed by the deputy Lieutenant Governor.

More information

- Bonaire 2050, a nature inclusive vision (pdf: 4,4 MB).

Tekst: Peter Verweij, Anouk Cormont, Jenny Lazebnik, Bertram de Rooij, Michiel van Eupen & Manuel Winograd, DCNA BioNews

Photo: MMBockstael Rubio

Figures: Robert Jan van Oosten & Bertram de Rooij